The early years

Electricity. We all take it for granted. It powers our homes, our businesses. It powers our entire lives. But this wasn’t always the case. The first quarter of the 20th century saw rapid developments in the technologies used to generate electricity. The high running costs of power stations at that time made electricity expensive for industry and a luxury only the wealthiest could afford for their homes. The problem wasn’t the power stations generating electricity, it was more to do with the way it was distributed. By 1920 London alone had more than 50 different systems to supply electricity with 24 different voltages and 10 different frequencies. Moving home could mean having to change all the electrical appliances! None of the many small power stations were interconnected, and each station needed its own backup reserve to avoid blackouts.

Formation of the Central Electricity Board (CEB)

This was all to change in December 1926 with the formation of the Central Electricity Board. Their task was to set up a “gridiron” of high voltage transmission lines to link the most efficient stations together. The aim of this was to provide a reliable electricity supply at an affordable price.

Despite strong opposition, the work of the CEB was a success. The power stations remained in the ownership of the power companies, but CEB engineers controlled generation using the most efficient plants. Reserve capacity could be pooled between interconnected stations meaning big savings – so much that the cost of electricity was halved.

Initially the system comprised of seven individual grids, all operating independently of one another. Connecting too many power stations to a single grid was deemed risky. This was to change when in 1938 it was realised the south didn’t have enough generating capacity to meet predicted needs, but the north had plenty. As an experiment the grids were interconnected for that winter, and in spring 1939 it was decided to keep them interconnected.

The interconnected grid was of great use during wartime, allowing blacked out London to supply the war-effort factories in the north, and minimising the effects of the Blitz when power stations were hit. The war took its toll, with minimal maintenance being carried out and coal stocks run down to dangerously low levels. The severe gales and big freeze of 1946 meant the coal supplies were not enough. The grid was the countries saving grace, but homes and businesses were ordered to switch off during mornings and afternoon. The following year the Electricity Act 1947 was put into place, to nationalise the electricity supply.

Nationalisation and the formation of the British Electricity Authority (BEA)

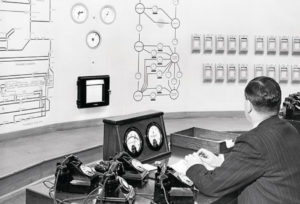

The reorganised industry came into being on 1st April 1948 and the British Electricity Authority (BEA) had a lot of work to do. Many of the 300 power stations the BEA had inherited were over 25 years old, and were mostly less than 8MW. The first priority was to get new plant into commission as quickly as possible. Increased generating capacity soon created another problem – the means to deliver the power supplies. The original grid had served the country well but to meet future needs the carrying capacity would need to be doubled. A supergrid network of 275kV was devised, capable of carrying six times the power and capable of being upgraded to 400kV. 14 operational divisions were established, each with a divisional controller to operate the grid in their area.

By the mid-1950s the new industry was well established, good progress was being made towards the targets the BEA had set. Demand was rising rapidly but a massive amount of new plant had been built – 8,000MW, a two-thirds increase. The first 40-mile section of 275kV supergrid was in operation, with another 1,500 miles of 132kV and 275kV line under construction.

In quick succession there were two major changes. Firstly, the South of Scotland Electricity Board was established, and the BEA renamed to the Central Electricity Authority as a result. The second change was to merge the Northwester Division with the Merseyside and North Wales Division, as an experiment in streamlining the organisation. These changes paved the way for an enquiry into the efficiency of the CEA and the divisional boards seized the chance to criticise what they saw as an overly-centralised operation and questioned the way it exercised responsibility as the central policy maker.

The Central Electricity Generating Board (CEGB)

The Central Electricity Generating Board (CEGB)

The result came in 1958 when a separate Electricity Council was formed to co-ordinate policy for the whole industry. The Central Electricity Authority was dissolved and in its place was the new Central Electricity Generating Board (CEGB), still with the task of achieving the most economical generation possible and delivering power supplies in bulk to the area boards for distribution.

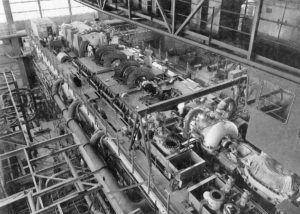

The pace of advancement escalated quickly after the CEGB was formed. When F. H. S. (Stanley) Brown took over as generation design engineer in 1953, one of his first proposals was for a 200MW set for High Marnham – bigger than any in Europe. This soon developed into plans for 300MW sets, giving more electricity from the same amount of fuel and pushing the frontiers of technology.

Within three years order were placed for eight 500MW sets even before any experience had been gained with the lower capacity. It was an ambitious programme, and some thought the advancements were escalating too quickly but fresh thought was needed along with the right kind of organisation to carry it through.

Throughout the 1950s it had been taken for granted that coal would be the primary fuel for power stations. That is until forecasts of increased requirements had both the NCB and government ministers worried. It seemed coal shortages of the time could last another 10 years. A start was made on converting some stations to oil firing, or dual coal and oil. At the time it was uneconomical but oil prices soon started to fall and further stations were converted to fire oil.

Another fuel was beginning to emerge around the same time. Nuclear power meant the CEGB could have a mixture of three fuels, and all the advantages that brought. The Nuclear Magnox reactors with their low running costs were always base load plants running 24 hours a day, while for the next 10 years system control engineers could use variations in coal and oil prices to help achieve other generation by the cheapest means.

The new high capacity stations required connections into the distribution network. Although the 275kV grid was well underway with the final 900 miles under construction, the new “super stations” would require the 400kV upgrades to be made. New 400kV connections would also need to be routed to the power stations. In 1961 the Transmission Construction Project Group was formed to build the supergrid.

Careful consideration was given to the locations of the new stations. Historically, power stations had been placed in areas of highest demand – amongst the most populated areas. The new supergrid made it cheaper to transport electricity than the equivalent cost to transport coal, allowing stations to be built near to the coal seams.

The first 2,000 MW station to come into service was Ferrybridge C in Yorkshire, followed by West Burton in the Midlands. Developments were being made at an exceptional pace, but not without problems. It took another 10 years to iron out all the kinks and develop adequate operating techniques. The instruments you see plastered all over equipment now-a-days wasn’t there when the turbines were first run. This learning curve paid off in the end, and as Gil Blackman said, “with that knowledge and experience in our locker we now have some of the best plant operating anywhere in the world”.

The ongoing technical challenges the CEGB faced required a new way of working, and that change came about in the 1970s. Regional engineering department were established, whereby power stations could call upon specialist services where maintenance tasks were out of the scope of the station staff. Transmissions sections were merged into larger districts, where transmission and generation were brought together under a Director of Production.

Towards the end of the 1970s the CEGB was starting to face another challenge. As the worldwide depression hit, the demand for electricity began to fall. A number of older, less efficient stations had already been closed down throughout the 1970s when demand increased at a slower pace than expected. Planners were confident demand would rise again, but environmentalists were arguing that future demand could be met using green alternatives such as wind power.

The first wind turbine was commissioned in 1982 at Carmarthen Bay in South Wales, with an output of 200 kilowatts – enough to power a small village. By 1989 the first one MW wind turbine had been commissioned in Kent, and plans were in place to build a wind park at Chapel Cynon, with 25 x 300 kilowatt turbines. Despite the advancements, it was still deemed the output of renewable sources of energy would not meet the resumed growth in electricity demand.

By the turn of the century the first wave of nuclear (Magnox) stations were approaching the end of their operational lifespans. The CEGB had dabbled with Advanced Gas-cooled Reactor (AGR) stations but they were running into problems and commissioning was delayed – by up to 15 years in the case of Dungeness. The decision was made to develop the Pressurised Water Reactors and by the early 1980s the first PWR was ordered.

The miners strikes of the 1980s put exceptional strain on the power generation industry. The CEGB had amassed a large stock of coal at its stations – 28 millions tonnes in fact, enough to last six months. The decision had to be made whether to burn the stocks of coal or switch predominantly to much more costly oil-fired generation, and oil was chosen. It proved to be a good decision, as the strikes lasted 12 months.

Privatisation of the Electricity Industry

A major change was announced in the Queen’s Speech to parliament in 1987. The CEGB was to be split up and the power industry would be privatised. The way this would happen was spelled out the following year in a white paper. The power stations would be split between two new companies, National Power and PowerGen. The distribution grid would become a third company independent of those generating power.

Initially, National Power was to inherit the nuclear power stations, but this plan was changed due to the fact most of the nuclear stations were near the end of their life and the company would not receive enough income to decommission them. It was decided a government owned company, Nuclear Electric would take on the role of running and decommissioning the ageing the Magnox reactors.

In 1990, the transmission activities of the CEGB were transferred to the National Grid Company plc, which was owned by the twelve regional electricity companies (RECs) through a holding company, National Grid Group plc. The company was first listed on the London Stock Exchange in 1995.

The transmission activities of the CEGB were transferred to the National Grid Company plc in 1990. Through a holding company, National Grid was owned by the twelve regional electricity companies (RECs). National Grid pursued major changes and mergers, and in October 2002 merged with Transco, the gas distribution network, to become National Grid Transco.

The Decline of Coal

21st April 2017. For many, that date marked the tipping point in the decline of electricity produced by burning coal. For the first time in 135 years, on that date the UK saw a 24 hour period where no coal was used to generate electricity. That’s quite a statement, considering for how long coal had been the major fuel source in the industry – just 5 years prior, coal was responsible for over 40% of the UKs electricity supplies.

Issued in October 2001, the Large Combustion Plant Directive (LCPD) aimed to reduce carbon emissions throughout Europe. The 2007 deadline allowed plants that did not comply with the strict emission limits to opt-out, whereby they could operate for a further 20,000 hours until 2015 at which point they had to close. The UKs carbon tax was increased in 2015, making many of the remaining plants uneconomical to operate. Only a handful of coal-fired power stations remained after that point.

The switch to low-carbon generation doesn’t come without cost – removing coal from the supply-mix will inevitably leave a void in the UKs generating capacity. Capacity from renewables such as wind and solar have seen a sharp rise in recent years, but nowhere near enough to fill the void. One new nuclear plant, Hinkley Point C is under construction, with others in the planning process. As new gas-fired plants are come online too, the future of the remaining coal power stations are most certainly numbered. The pace at which the last surviving plants will close remains to be seen.

Final Word

The electricity distribution network as we know it today has developed and expanded over time, from thousands of isolated systems in the early 1900s to a huge fully integrated system at the heart of modern living. The electricity generated by the power stations around the UK have also seen many changes, not only in their size, peaking with the giant coal power stations capable of outputting many gigawatts of electricity. An effort to reduce global carbon emissions ultimately spelled the end for these behemoths, as we move into an age of low-carbon electricity production. The industry will continue to evolve, but the huge coal burning giants of the past will remain, in our memories, in our hearts, and through websites such as this one, as a testament to the engineering marvels of years gone by.